This month, we honour Félicette, the first cat in space, as we look at some of the most interesting journeys to the stars made by non-human animals.

Human beings have been sending animals into space since before we invented spaceflight.

More than 20 years before NASA’s Apollo 11 astronauts walked on the Moon, the US Air Force began studying the effects of spaceflight, radiation, and a zero-gravity environment. And it started with fruit flies and ballistic missiles in 1946.

Fruit flies might seem an odd first choice, but they share a significant number of genes with humans and other organisms. By looking at genes in fruit flies, scientists can find and compare similar genes in other, more complex, organisms.

Studies show that fruit flies exposed to both radiation and space flight experience faster ageing and genetic mutations. A 2017 study showed fundamental differences in the hearts of fruit flies that had lived in space for several weeks, compared to Earthbound specimens. These findings have valuable implications for long-term human habitation on the Moon or Mars.

Ham the primate pioneer

In 1961, Ham the Astrochimp became the first great ape to boldly go where no primate had gone before.

Because a chimpanzee’s response time is very similar to that of most humans, two-year-old Ham trained to perform simple, timed tasks in response to electric lights and sounds.

Ham’s 16-minute journey to space aboard Mercury-Redstone 2 took him 254km above the Earth, and his successful ability to perform tasks mid-flight helped pave the way for astronaut Alan Shepard’s flight a few months later.

After retiring from NASA in 1963, Ham transferred to the National Zoo in Washington, DC.

Who let the dogs out

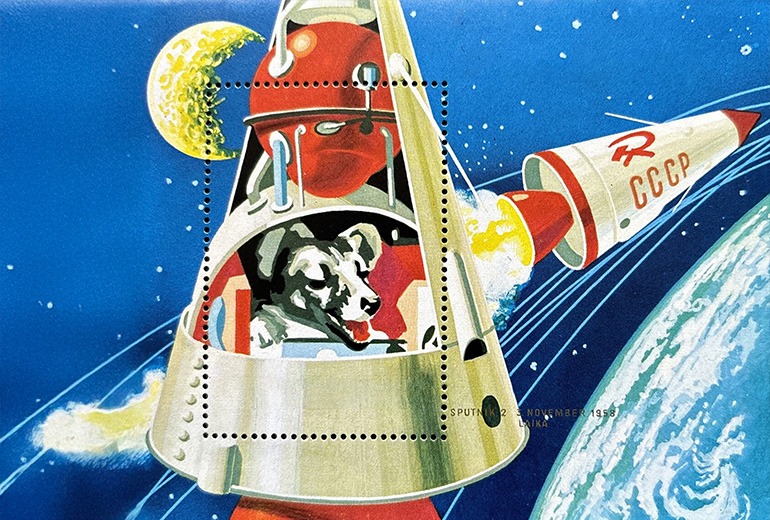

The USSR launched Sputnik 2 in November 1957, mere weeks after the first artificial Earth satellite.

Among its successes, Sputnik 2 was the first spacecraft to carry an animal into orbit: the canine cosmonaut Laika. The second Sputnik’s five-month journey was one of nearly 60 Soviet space-dog missions.

Laika’s mission training included preparing her for the cramped space module and standing still for long periods, as well as wearing a specially designed space suit. She was also placed in simulators that mimicked a rocket launch and rode in centrifuges to replicate the high acceleration of a rocket launch.

Soviet scientists didn’t expect Laiks to survive her mission, but it was only in 2022 that authorities admitted she’d died of hyperthermia on the craft’s fourth orbit, just hours into the flight.

Spiders in space

NASA’s 1973 Skylab 3 mission carried two female European garden spiders into space. The goal was to test whether spiders would spin webs in space and whether these webs would be the same as on Earth.

Scientists consider it very important that their spiders built webs at all in zero gravity. Unlike on Earth, the spiders built symmetrical webs, and the silk of the Skylab spiders was thinner than that of webs seen on Earth, possibly due to the absence of gravity.

Star fish

Spiders aren’t the only animals that seem to be confused by zero gravity. In 1991, NASA’s Space Shuttle Columbia’s STS-40 mission was the first dedicated solely to life sciences, carrying among its cargo 2,478 jellyfish*.

Since humans and jellyfish use similar functions to sense gravity, studying jellyfish development and behaviour in space could provide valuable info on how humans might cope when growing up in microgravity.

Studies have found that jellyfish born in space had difficulty swimming on returning to Earth. Similarly, jellyfish born on Earth and those born in microgravity struggled with orienting themselves in space.

In 2024, four zebrafish spent 43 days in orbit aboard China’s Tiangong space station. Although the zebrafish were all reportedly in good condition, scientists noticed them swimming abnormally in microgravity, including swimming upside down and in circles.

*yes, we know jellyfish aren’t fish, but “fish” isn’t a scientifically valid group of animals, either.

In 1963, Félicette helped establish France as the world’s third civilian space agency, after the USA and USSR.

The stray Parisian cat wasn’t the first mammal in orbit; that honour goes to Laika, and Laika’s successors, Belka and Strelka, who were first to safely return to Earth from orbit. However, Félicette’s mission focused on studying her nervous system.

French scientists already had extensive neurological data on cats, and Félicette’s brain activity was monitored continuously throughout her flight. Félicette was understandably stressed by the rocket launch, and the cat experienced up to 9.5 g-forces — nearly twice what Apollo astronauts faced during their lunar missions, but in-flight data confirmed that Félicette remained calm.

Félicette’s mission not only provided a comparison for the results of test missions with dogs and primates, but her collected neurological data also made clear that spaceflight didn’t cause other neurological damage that wasn’t immediately apparent.

In 2019, the Israeli SpaceIL organisation launched its Beresheet spacecraft, aiming to land the first privately funded spacecraft on the Moon.

The Arch Mission Foundation, a non-profit organisation, included with Beresheet tens of millions of pages of archives containing scientific and cultural knowledge in various languages, samples of human DNA, and thousands of microscopic creatures from Earth.

Tardigrades, also known as water bears, can survive temperature extremes, air deprivation, dehydration, starvation, and, most notably, the vacuum of space and cosmic radiation.

48 days after its mission began, Beresheet started firing its engines for a soft lunar landing, but the spacecraft’s gyroscope failed, and it crashed into the Moon, scattering its library across the lunar surface.

Water bears need water and an atmosphere to thrive — both things the Moon lacks — but if they survived the impact, the microscopic ‘bears’ could survive for decades.

Jay Chesters

Jay Chesters is a wordsmith with a little bit of a thing for the stars. As a cosmic storyteller with a love for astronomy and space that's out of this world, Jay’s always eager to share his knowledge and passions.

Take your stargazing to the next level

Keen to learn more about astronomy and how to get more from your telescope? Click the button for more info on our telescope & astronomy classes where everyone is welcome.